Stocks and Bonds: Primer

This section describes the basic structural characteristics and features of the two major investment asset classes, stocks and bonds. It does not examine their historical investment performance, which we first address in the "Stocks and Bonds - Return Characteristics" section.

Before we start, here are some definitions and clarifications so that we’re all on the same page:

Stocks: also referred to as shares or equities

Stock owners: also referred to as stockholders, shareholders or stock investors

Bonds: also referred to as fixed income

Bond owners: also referred to as bondholders or bond investors

Investment Return: a payment to or accumulation of value to an investor, over and above their investment's original value

Before we start, here are some definitions and clarifications so that we’re all on the same page:

Stocks: also referred to as shares or equities

Stock owners: also referred to as stockholders, shareholders or stock investors

Bonds: also referred to as fixed income

Bond owners: also referred to as bondholders or bond investors

Investment Return: a payment to or accumulation of value to an investor, over and above their investment's original value

-

Summary

-

Main

-

Details

<

>

Bonds

Stocks

- Bonds are securities with the same characteristics as loans, the extension of credit from an investor (lender) to an issuer (borrower). The issuer then makes ongoing interest payments and also repays the bond’s par value or principal (its original loan amount), with payments typically made according to a fixed rate and schedule.

- A bond’s source of return is its interest payments.

- The main issuers of bonds are governments and corporations.

- A bond’s fixed schedule of payment timing and amounts provides greater certainty to investors, but it still presents the risk that its issuer may not make full payment.

- Central governments are usually thought to be the safest bond issuers because of their broad tax base and taxation authority. However, a central government can also have its central bank monetize the government’s debt (“run the printing presses”), which causes higher inflation and harms bondholders, who are repaid but in much less valuable currency. The latter situation is fortunately quite rare.

- State, provincial or municipal governments have narrower tax bases and so their bonds are usually viewed as riskier than those issued by their corresponding central government.

- Corporate bonds are viewed as riskier yet than government bonds because corporations have no taxing authority and face competition. But following a default, bond investors may fare better with a corporate than a government bond because they can take effective control of a corporation’s assets, but cannot do the same with a sovereign country or legal jurisdiction.

- Repayment uncertainty increases with a bond’s term to maturity; more things can go wrong over longer periods.

Stocks

- Stocks are securities that confer ownership and are typically issued by corporations.

- A stock’s ultimate source of return is the current and future profit (also called net income or earnings) the corporation is expected to generate. Profit can be paid to its owners as dividends, retained in the company to help pay for its future growth, or any combination of the two.

- Stock ownership is inherently less certain than bond ownership, even of bonds issued by the same corporation, because owners get paid last.

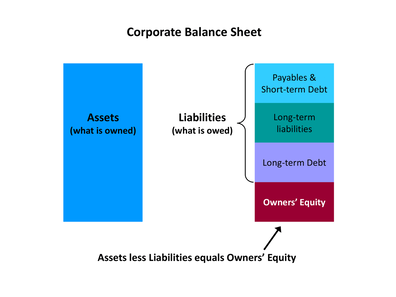

- In the company’s balance sheet (Levels; a snapshot), owners’ equity is the last in line in the event of receivership and restructuring. Owners get paid from the proceeds of asset sales only after all other claimants, including creditors (bond holders), have received their proceeds.

- In the company’s income statement (Flows; a measure over a period of time), owners’ profit is what remains from company revenue after all other costs – employees, suppliers, maintenance, interest to creditors/bond holders, taxes – have first been paid.

- Because they’re paid last, stock owners act as a company’s and the economy’s “shock absorber”.

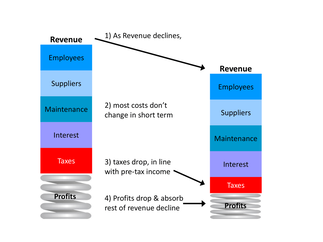

- In the short term, most costs other than taxes are fixed and so a revenue downturn is absorbed mainly by a drop in owners’ profit. Other costs will also adjust if the downturn ensues.

- The same process works in reverse when a company’s operations are better than expected: most other costs don’t immediately rise, and so a revenue upturn translates in to higher profit.

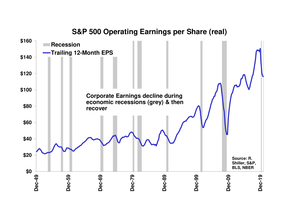

- In every US recession but one since 1950, aggregate corporate earnings fell during the recession and rose thereafter.

- Investors “put the cart before the horse” if they conclude that stocks are riskier than bonds mainly because stock prices are more volatile. Stocks are inherently riskier than bonds by design. In return for the uncertainty of being the last to be paid, stock owners also participate in the company’s success whereas bondholders receive, at most, their interest and principal payments.

Bonds

Bonds are securities with the same characteristics as loans, the extension of credit by an initial investor (lender) to a bond issuer (borrower). The subsequent repayments by the bond issuer are typically made according to a pre-determined schedule and in set amounts. The fixed nature of bonds’ repayment schedule and amounts gives rise to their nickname of “fixed income”, though for consistency we refer to them only as bonds.

The source of a bond’s return is its ongoing interest payments, which are nearly always fixed in size at the time of bond issuance. A bond’s principal (its initial loan amount) is also repaid, usually in one lump amount upon the bond’s maturity date when the bond is retired by its issuer.

The major issuers of bonds are governments and corporations. Bonds issued by central governments are usually assumed to be quite safe and have a high likelihood of full payment of interest and principal, due mainly to a central government’s broad tax base and its authority to increase taxes if needed to cover its bond payments.

A central government can also have the country’s central bank print more money (or its electronic equivalent) to cover the central government’s debt payments. This is fortunately quite rare but when it occurs is very detrimental to bond investors, as they are repaid with a currency whose purchasing power is badly reduced by high inflation. (The resulting high or even hyperinflation is also very damaging to the country’s economy and its citizens.)

Non-central governments such as state, provincial or municipal governments have a narrower tax base and fewer taxation powers than a central government. Their bonds therefore have a higher likelihood of non-payment than those issued by the same country’s central government.

Bonds issued by corporations also carry the risk that the company might be unable to make its bond payments. Unlike governments, corporations cannot simply raise taxes on their customers in the event of a revenue shortfall, and they also face ongoing competition from other companies. However, corporate bond investors often have better remedies available than government bond investors in the event of payment default. Creditors cannot “take posession” of a defaulting sovereign country or its assets in the same manner as they can those of a defaulting corporation.

Although bonds’ fixed schedules of interest and principal payment give greater certainty to investors, bonds also carry uncertainty about their issuer’s ability to make those payments, or about the potential to receive payment whose value is eroded by unexpected inflation. The uncertainty associated with bond payments increases with a longer term to maturity; more things can go wrong over a longer period of time.

The source of a bond’s return is its ongoing interest payments, which are nearly always fixed in size at the time of bond issuance. A bond’s principal (its initial loan amount) is also repaid, usually in one lump amount upon the bond’s maturity date when the bond is retired by its issuer.

The major issuers of bonds are governments and corporations. Bonds issued by central governments are usually assumed to be quite safe and have a high likelihood of full payment of interest and principal, due mainly to a central government’s broad tax base and its authority to increase taxes if needed to cover its bond payments.

A central government can also have the country’s central bank print more money (or its electronic equivalent) to cover the central government’s debt payments. This is fortunately quite rare but when it occurs is very detrimental to bond investors, as they are repaid with a currency whose purchasing power is badly reduced by high inflation. (The resulting high or even hyperinflation is also very damaging to the country’s economy and its citizens.)

Non-central governments such as state, provincial or municipal governments have a narrower tax base and fewer taxation powers than a central government. Their bonds therefore have a higher likelihood of non-payment than those issued by the same country’s central government.

Bonds issued by corporations also carry the risk that the company might be unable to make its bond payments. Unlike governments, corporations cannot simply raise taxes on their customers in the event of a revenue shortfall, and they also face ongoing competition from other companies. However, corporate bond investors often have better remedies available than government bond investors in the event of payment default. Creditors cannot “take posession” of a defaulting sovereign country or its assets in the same manner as they can those of a defaulting corporation.

Although bonds’ fixed schedules of interest and principal payment give greater certainty to investors, bonds also carry uncertainty about their issuer’s ability to make those payments, or about the potential to receive payment whose value is eroded by unexpected inflation. The uncertainty associated with bond payments increases with a longer term to maturity; more things can go wrong over a longer period of time.

Stocks

Stocks are securities that confer ownership and are typically issued by a corporation. The source of a stock’s return is a corporation’s ability to generate profit through its operations, both in the present and in the future. The company’s profits or earnings can be paid to its owners as dividends, retained in the company to help pay for its future growth, or any combination of the two. Shareholders collectively own the corporation’s assets, less its liabilities, and through their appointment of the company’s directors also exercise control of the corporation.

|

The benefits of stock ownership are inherently uncertain because shareholders get paid last. Viewed on a Levels or snapshot-in-time basis, as in the simple balance sheet to the right, shareholders own the company’s assets on the left side less all its liabilities on the right side. Owners are thus positioned at the bottom of the “pecking order” of claimants on the company’s assets. It's no coincidence that Short- and Long-term Debt, which include bonds, are both positioned above Owners’ Equity. If the firm ever fails and is put into receivership and restructured, its bondholders get paid completely before its stockholders get paid at all. |

Shareholders also lie at the bottom of the pecking order when viewed on a Flows basis, i.e. the company’s operations measured over a period of time. As shown in the simple income statement below, a company’s profit, also commonly referred to as its net income or earnings, equals its revenues less its expenses or costs:

Revenue

less Costs:

Employees

Suppliers

Maintenance

Interest

Taxes

equals Profit

It’s again no coincidence that interest payments appear above owners’ profit: in each period, the company’s bondholders and other lenders get paid before its owners. This provides more certainty to bondholders but at the expense of stockholders.

Stockholders provide a valuable function to the economy because, via the profit mechanism, they absorb most of the shock when the company or the broader economy experiences a downturn.

|

The diagram to the right illustrates this during a downturn. The company’s revenue is at the top, with its various costs below and profit at the bottom. In the right half of the diagram the company receives less revenue than in the left half: due to a recession, for example, it sells fewer products and/or can only sell them for a lower price. Because in the short term the company’s costs (other than taxes) don’t adjust to its lower revenue, the downturn is absorbed mainly by its lower profits, shown by the compressed spring. |

Over a longer period the company’s other costs will also adjust. Because it sells fewer products or services, it will require fewer employees and might pay lower wages or salaries, it will require fewer supplies and may pay its suppliers lower prices, it will not have to maintain as many fixed assets or invest as much in new capacity, etc. But stockholders, through the profit mechanism, nearly always take the first hit.

The same process works in reverse when the company experiences good fortune: in the short term its costs (other than taxes) remain fixed, and its profit expands commensurately.

|

The chart to the right shows this process over the last 70 years. The real (inflation-adjusted) operating earnings or profit of the S&P 500 index of large US companies are shown in blue. In every US recession other than one (recessions in grey), companies’ earnings declined. Earnings more than recovered after each recession, albeit at a different pace each time. |

Investors often view stocks as riskier than bonds mainly because stock prices exhibit greater fluctuation. But this puts the cart before the horse: stocks are inherently riskier than bonds by design. Whether viewed on a Levels or Flows basis, a company’s stockholders benefit only after the same company’s bondholders and other claimants/costs are paid. In return for bearing the uncertainty of being the last to be paid, stockholders participate in a corporation’s success whereas bondholders’ participation is limited to their interest and principal payments.

1a) Every rule has exceptions and bonds are no different. Not every bond’s interest payments are fixed in advance. One subset of bonds, called floating-rate bonds, pays interest according to relative to a reference interest rate, using a formula set in advance. Because the reference interest rate changes aren’t known in advance, a floating-rate bond’s payments are also not known in advance; they “float” along with changes in the reference rate.

1b) Some bonds also repay some or all of their principal on an ongoing basis, rather than as one lump sum upon maturity. An example is a non-bulletized mortgage-backed security (MBS). Nearly all mortgage loans, whether residential or commercial, require the borrower to pay both interest and some principal each month. An MBS is just a fixed-income security issued by an investment fund or pool that holds mortgages as its underlying assets. The pool’s monthly payments to the MBS owner are therefore a pass-through of the pool’s monthly collections from its underlying mortgage loans, which by necessity include both interest and principal paydown. An MBS is an exception in another way, as well: its payments are typically made on a monthly basis rather than semi-annually like most other bonds.

The “non-bulletized” jargon in the prior paragraph refers to an MBS whose payments reflect those of its underlying mortgage loans in their original form. Because many bond investors prefer standardization, MBS sponsors often “bulletize” their MBS payments by using derivatives to transform the underlying mortgages’ monthly, principal-amortizing payments into semi-annual interest-only payments, with principal repaid only at maturity. For example, the Canada Housing Trust’s Canada Mortgage Bonds reflect this bulletized treatment and pay interest (and no principal) semi-annually, even though their underlying assets consist of NHA MBS which in turn consist of monthly-pay, principal-amortizing residential mortgages guaranteed by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC).

1c) Some bonds make no interest payments at all. Strip bonds, sometimes called pure discount bonds, are issued at a discount to their maturity (par) value, and their movement from their initial or interim price upwards to their par value at maturity represents an investor’s return. Strip bonds acquired their name because they were initially created when investment dealers “stripped” the semi-annual coupons from government-issued bonds, and then sold the coupons separately. Each coupon entitled its owner to a one-time interest payment at the coupon date, and after being separated from the rest of the bond, traded at a discount to its payment amount.

1d) Some bonds allow their owners to participate in a company’s good fortune, but not through a direct claim on corporate profits. Rather, these bonds are called “convertibles” and as their name implies, give the owner the right to convert their bond into a certain number of the company’s shares upon surrender of the bond. If the value of shares received upon conversion is higher than the bond’s value, an investor will typically convert their bond into shares.

1e) Not all bonds are harmed by unexpectedly high inflation. One category of bonds, commonly called Real Return Bonds (RRBs) but also referred to as Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) in the United States, makes interest and principal payments that are adjusted upwards (or downwards) by inflation, where the latter is measured by changes in the consumer price index (CPI). An RRB protects a bond investor from unexpectedly high inflation because the RRB’s payments automatically adjusts upwards with CPI, regardless of whether CPI rises faster, slower, or at the same rate as expected at the time of bond purchase. The RRB’s payments can even fall if CPI falls – though this is an infrequent occurrence!

1f) Some bonds have an uncertain maturity date. For example, a bond issuer may also give itself the right to “call” and retire a bond at a certain price, prior to its formal maturity date. The issuer will typically call the bond only if interest rates decline and it can call the higher-yielding bond and replace it with a lower-yielding bond, and thereby save itself the difference between the higher old and the lower new interest rates.

Other bonds have a maturity date that can be lengthened (extended) or shortened (retracted) at the owner’s option.

1g) None of these exceptions invalidates the general rule that bond payments are structured to impart significant certainty to investors, and that the preponderance of bonds have fixed payment amounts and payment dates.

2) When a corporation issues very large amounts of debt, that debt starts to take on characteristics of the company’s stock and bondholders start to share the downside risk with its stockholders. On a Levels basis (balance sheet), during a restructuring there may not be enough assets to cover all the bondholders’ payments. On a Flows basis, during a downturn there may not be enough revenue available to cover all interest payments.

3) A hybrid asset class called Preferred Shares lies between bonds and stocks on the balance sheet and in the income statement. On a Levels basis (the balance sheet), owners of preferred shares are typically positioned below bonds and other creditors but above common shareholders during a restructuring.

On a Flows basis, preferred shares typically don’t have voting rights but pay a (nearly) set dividend. Any preferred share dividends missed or skipped in the past must be paid first, before common shareholders can be paid a dividend. When a preferred share dividend is missed it does not automatically trigger a default, unlike when an interest payment to bondholders is missed.

4) Not all shares carry the same voting rights. Some companies structure their shares into two or more classes, each with different voting rights.

5) In addition to dividends, share buybacks are a method of distributing profits and cash to shareholders. On the company’s balance sheet, buybacks are identical to dividends: both reduce cash on the left side and owners’ equity on the right side by an identical amount. However, buybacks also reduce the company’s shares outstanding, which raises accounting performance measures such as Earnings Per Share by lowering such measures' denominator.

1b) Some bonds also repay some or all of their principal on an ongoing basis, rather than as one lump sum upon maturity. An example is a non-bulletized mortgage-backed security (MBS). Nearly all mortgage loans, whether residential or commercial, require the borrower to pay both interest and some principal each month. An MBS is just a fixed-income security issued by an investment fund or pool that holds mortgages as its underlying assets. The pool’s monthly payments to the MBS owner are therefore a pass-through of the pool’s monthly collections from its underlying mortgage loans, which by necessity include both interest and principal paydown. An MBS is an exception in another way, as well: its payments are typically made on a monthly basis rather than semi-annually like most other bonds.

The “non-bulletized” jargon in the prior paragraph refers to an MBS whose payments reflect those of its underlying mortgage loans in their original form. Because many bond investors prefer standardization, MBS sponsors often “bulletize” their MBS payments by using derivatives to transform the underlying mortgages’ monthly, principal-amortizing payments into semi-annual interest-only payments, with principal repaid only at maturity. For example, the Canada Housing Trust’s Canada Mortgage Bonds reflect this bulletized treatment and pay interest (and no principal) semi-annually, even though their underlying assets consist of NHA MBS which in turn consist of monthly-pay, principal-amortizing residential mortgages guaranteed by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC).

1c) Some bonds make no interest payments at all. Strip bonds, sometimes called pure discount bonds, are issued at a discount to their maturity (par) value, and their movement from their initial or interim price upwards to their par value at maturity represents an investor’s return. Strip bonds acquired their name because they were initially created when investment dealers “stripped” the semi-annual coupons from government-issued bonds, and then sold the coupons separately. Each coupon entitled its owner to a one-time interest payment at the coupon date, and after being separated from the rest of the bond, traded at a discount to its payment amount.

1d) Some bonds allow their owners to participate in a company’s good fortune, but not through a direct claim on corporate profits. Rather, these bonds are called “convertibles” and as their name implies, give the owner the right to convert their bond into a certain number of the company’s shares upon surrender of the bond. If the value of shares received upon conversion is higher than the bond’s value, an investor will typically convert their bond into shares.

1e) Not all bonds are harmed by unexpectedly high inflation. One category of bonds, commonly called Real Return Bonds (RRBs) but also referred to as Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) in the United States, makes interest and principal payments that are adjusted upwards (or downwards) by inflation, where the latter is measured by changes in the consumer price index (CPI). An RRB protects a bond investor from unexpectedly high inflation because the RRB’s payments automatically adjusts upwards with CPI, regardless of whether CPI rises faster, slower, or at the same rate as expected at the time of bond purchase. The RRB’s payments can even fall if CPI falls – though this is an infrequent occurrence!

1f) Some bonds have an uncertain maturity date. For example, a bond issuer may also give itself the right to “call” and retire a bond at a certain price, prior to its formal maturity date. The issuer will typically call the bond only if interest rates decline and it can call the higher-yielding bond and replace it with a lower-yielding bond, and thereby save itself the difference between the higher old and the lower new interest rates.

Other bonds have a maturity date that can be lengthened (extended) or shortened (retracted) at the owner’s option.

1g) None of these exceptions invalidates the general rule that bond payments are structured to impart significant certainty to investors, and that the preponderance of bonds have fixed payment amounts and payment dates.

2) When a corporation issues very large amounts of debt, that debt starts to take on characteristics of the company’s stock and bondholders start to share the downside risk with its stockholders. On a Levels basis (balance sheet), during a restructuring there may not be enough assets to cover all the bondholders’ payments. On a Flows basis, during a downturn there may not be enough revenue available to cover all interest payments.

3) A hybrid asset class called Preferred Shares lies between bonds and stocks on the balance sheet and in the income statement. On a Levels basis (the balance sheet), owners of preferred shares are typically positioned below bonds and other creditors but above common shareholders during a restructuring.

On a Flows basis, preferred shares typically don’t have voting rights but pay a (nearly) set dividend. Any preferred share dividends missed or skipped in the past must be paid first, before common shareholders can be paid a dividend. When a preferred share dividend is missed it does not automatically trigger a default, unlike when an interest payment to bondholders is missed.

4) Not all shares carry the same voting rights. Some companies structure their shares into two or more classes, each with different voting rights.

5) In addition to dividends, share buybacks are a method of distributing profits and cash to shareholders. On the company’s balance sheet, buybacks are identical to dividends: both reduce cash on the left side and owners’ equity on the right side by an identical amount. However, buybacks also reduce the company’s shares outstanding, which raises accounting performance measures such as Earnings Per Share by lowering such measures' denominator.