Secondary Markets & Investor Implications

-

Summary

-

Main

-

Details

<

>

Background

Price Movements and Emotion

Trading's Zero-sum Nature

- Nearly all stock and bond trades occur in a secondary market, i.e. among entities other than the security’s original issuer. Trades on a secondary market do not change the number of securities outstanding.

- Secondary markets take many forms. Stocks trade very frequently and their trading prices and volumes are widely disseminated. Bonds trade much less frequently, their prices are more difficult to obtain, and some bonds are available only to institutional and not retail buyers.

- Trading costs dropped greatly over the last several decades, particularly for stocks.

Price Movements and Emotion

- The continual and sometimes wild fluctuations observed in secondary market prices have two major causes.

- News about an underlying security’s issuer affects the security’s price, but news is released at a much lower frequency than price changes.

- Changes in buyer and seller emotion and sentiment – for any reason – cause most of the ongoing price changes, and emotions can temporarily become very pronounced.

- A long-term investor who cares little about short-term price swings can still be harmed by them.

- A planned sale to raise a fixed dollar amount for consumption requires the sale of a greater portion of the portfolio, if prices fall just before the sale. The remaining portfolio has less value with which to benefit from a price upturn.

- An investor who makes a security purchase will own fewer securities if prices jump upwards just before their purchase.

- A solution, for an investor who knows they have a large investment transaction upcoming, is to split the transaction into several smaller pieces over several days or weeks.

- Price movements due to extreme emotions can also damage a long-term investor if they abandon their plans and sell after security prices drop (because they fear further price drops), and then buy back after prices rise, when markets "feel safe”. This is the equivalent of selling low and buying high.

- Interest payments and corporate profits and their growth, not transient emotion-driven price changes, are the largest determinants of long-term bond and stock returns and are illustrated in the Bond and Stock Return Components sections.

Trading's Zero-sum Nature

- Unlike the “secondary market” sale of a used car by its original owner, which can occur even if buyer and seller both completely agree about the car’s quality, trades of financial securities in a secondary market are characterized almost entirely by disagreement.

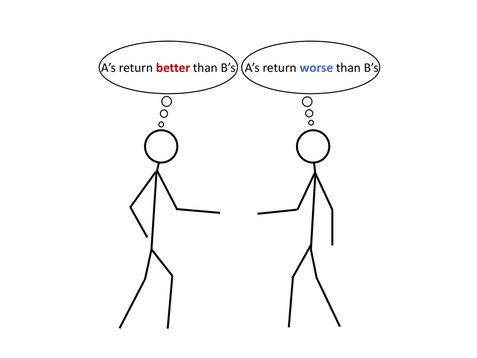

- The first investor believes the security they’re buying (A) has better future prospects than the security they’re selling (B) to fund its purchase. The counterparty, who sells A and buys B, believes the exact opposite.

- After the transaction, security A’s return will be either better or worse than security B’s.

- Trading is therefore a zero-sum game in which only one of the trade's parties will be correct. After subtracting transaction costs, trading becomes a negative-sum game.

- Even a long-term investor must trade to convert cash savings into securities and again when they sell those securities to use the proceeds for consumption, or to adjust their investment holdings. But trading should be kept to a minimum: if one of the two counterparties will be proven wrong, it’s unsafe to assume it will always be the other person!

- Investing – owning stocks and bonds for the returns they generate over time through profits and interest – is a positive-sum game at which every participant can succeed, even those who underperform the broad market index, so long as their investment returns meet their goals.

Background

Nearly all stock and bond trades occur in a secondary market, which consists of people or entities other than the securities' original issuers. One or more non-issuers purchase a security from its issuer when it's first issued, and subsequent trading occurs almost entirely among non-issuers. Trades on a secondary market do not change the number of securities outstanding.

Secondary markets take many forms depending on the security. Stocks trade very frequently and their trading prices and volumes are widely disseminated. Bonds trade much less frequently, their prices are more difficult to obtain, and some bonds are available only to institutional and not to retail buyers.

The cost of trading in secondary markets dropped greatly over the last several decades, particularly for stocks. For example, by 2020 it typically cost $10 or less in total commission, plus the bid/ask spread on quoted prices, to execute a stock trade from within a Canadian discount brokerage account.

This section does not delve into secondary markets' finer operational details but instead focuses on their two most important investment implications.

Secondary markets take many forms depending on the security. Stocks trade very frequently and their trading prices and volumes are widely disseminated. Bonds trade much less frequently, their prices are more difficult to obtain, and some bonds are available only to institutional and not to retail buyers.

The cost of trading in secondary markets dropped greatly over the last several decades, particularly for stocks. For example, by 2020 it typically cost $10 or less in total commission, plus the bid/ask spread on quoted prices, to execute a stock trade from within a Canadian discount brokerage account.

This section does not delve into secondary markets' finer operational details but instead focuses on their two most important investment implications.

Price Movements and Emotion

Security prices in the secondary markets, particularly stock prices, fluctuate almost continually and sometimes by extreme amounts in very short periods. What causes these price changes?

News about a security’s issuer affects the security’s price, but companies report their financial results once only every three months and so those results alone seem unlikely to cause price changes every minute of every day. Because a secondary market has a stream of trades constantly occurring, the price of the last trade reflects the sentiments of both counterparties - who, being human, are subject to the occasional emotional swing.

To a long-term investor, large price swings driven by short-term emotional extremes are an unavoidable side effect of owning securities traded in a secondary market. For example, a stock investor who planned to sell some holdings and use the proceeds for consumption (not for reinvestment) can be caught at the vagaries of negative market sentiment, if prices just recently dropped sharply. The investor must sell more securities at a lower price (a greater portion of their portfolio’s value) in order to fund their consumption, and their remaining portfolio has less value with which to benefit from prices’ eventual upturn.

Similarly, an investor who makes a security purchase from their employment bonus payment will own fewer securities if prices jump upwards just before the purchase.

Fortunately, these situations tend to even out over the course of an investor’s lifetime. Furthermore, an investor who knows they have a large investment transaction upcoming can split the transaction into several smaller pieces occurring over several different days or weeks, thereby minimizing the chance of being unduly harmed by any single short-term price movement.

Extreme price movements caused by extreme emotions can also damage an investor’s portfolio if they join the panic (or euphoria!) and abandon their long-term investment plan at an inopportune time. A classic mistake is for investors, upon a sharp market decline, to project the decline into the future and to forget that prices will likely reverse after the emotional extreme that caused decline also subsides. Unless an investor needs to immediately sell holdings for consumption purchases, in which case they should use the staging plan mentioned in the prior paragraph, it’s best to do nothing during market drops. A fear-driven sale runs the risk of turning a temporary market decline into a permanent loss, as the investor sells low and buys back high.

We learned in the in the Primer section that the ultimate source of returns for bonds is their interest payments and for stocks is their current and future profit/earnings. We’ll see in the Bond and Stock Return Components sections that these components, rather than transient swings in market sentiment, are the largest determinants of long-term security returns.

News about a security’s issuer affects the security’s price, but companies report their financial results once only every three months and so those results alone seem unlikely to cause price changes every minute of every day. Because a secondary market has a stream of trades constantly occurring, the price of the last trade reflects the sentiments of both counterparties - who, being human, are subject to the occasional emotional swing.

To a long-term investor, large price swings driven by short-term emotional extremes are an unavoidable side effect of owning securities traded in a secondary market. For example, a stock investor who planned to sell some holdings and use the proceeds for consumption (not for reinvestment) can be caught at the vagaries of negative market sentiment, if prices just recently dropped sharply. The investor must sell more securities at a lower price (a greater portion of their portfolio’s value) in order to fund their consumption, and their remaining portfolio has less value with which to benefit from prices’ eventual upturn.

Similarly, an investor who makes a security purchase from their employment bonus payment will own fewer securities if prices jump upwards just before the purchase.

Fortunately, these situations tend to even out over the course of an investor’s lifetime. Furthermore, an investor who knows they have a large investment transaction upcoming can split the transaction into several smaller pieces occurring over several different days or weeks, thereby minimizing the chance of being unduly harmed by any single short-term price movement.

Extreme price movements caused by extreme emotions can also damage an investor’s portfolio if they join the panic (or euphoria!) and abandon their long-term investment plan at an inopportune time. A classic mistake is for investors, upon a sharp market decline, to project the decline into the future and to forget that prices will likely reverse after the emotional extreme that caused decline also subsides. Unless an investor needs to immediately sell holdings for consumption purchases, in which case they should use the staging plan mentioned in the prior paragraph, it’s best to do nothing during market drops. A fear-driven sale runs the risk of turning a temporary market decline into a permanent loss, as the investor sells low and buys back high.

We learned in the in the Primer section that the ultimate source of returns for bonds is their interest payments and for stocks is their current and future profit/earnings. We’ll see in the Bond and Stock Return Components sections that these components, rather than transient swings in market sentiment, are the largest determinants of long-term security returns.

Trading's Zero-sum Nature

The trade of a financial security in a secondary market is unlike a transaction in any other market.

For example, if the buyer prefers to drive used vehicles and if the seller prefers to drive new vehicles, then a used car (the “secondary market” for cars) will change hands between them despite complete agreement between buyer and seller about the car’s quality.

Trades of financial assets in a secondary market, however, are characterized almost entirely by disagreement between the trade’s counterparties.

For example, if the buyer prefers to drive used vehicles and if the seller prefers to drive new vehicles, then a used car (the “secondary market” for cars) will change hands between them despite complete agreement between buyer and seller about the car’s quality.

Trades of financial assets in a secondary market, however, are characterized almost entirely by disagreement between the trade’s counterparties.

|

The first investor believes the security being bought, security A, has better return prospects than the security being sold to fund the purchase, security B. For the first investor to buy A and sell B, their counterparty must do the opposite and sell A and buy B, because trades don't change the number of securities. This means their counterparty also believes the opposite, that security A will do worse than security B. After the transaction, security A’s return will be either better or worse than security B’s; it will not simultaneously be both. |

Trading in a secondary market is therefore a zero-sum game in which only one of the trade's parties will be correct. After subtracting transaction costs, trading becomes a negative-sum game. The Details tab explains how these results hold in a secondary market containing multiple different securities and investors, including investors with different time horizons.

Does this mean investors shouldn’t trade? Definitely not: an investor must trade in order to convert their cash savings into securities, and then again to sell those securities and use the proceeds for consumption. An investor must also trade if there is sufficient reason to adjust their investment holdings. But the lesson is that trading should be done infrequently: because one of the two counterparties will be proven wrong, it’s unsafe to assume it will always be the other person!

In contrast to the zero-sum nature of trading, investing – owning stocks and bonds for the returns they generate over time through their profits and interest – is a positive-sum game at which every participant can succeed. Even an investor whose portfolio underperforms the broad market index may still be successful, so long as their investment returns meet their goals.

Does this mean investors shouldn’t trade? Definitely not: an investor must trade in order to convert their cash savings into securities, and then again to sell those securities and use the proceeds for consumption. An investor must also trade if there is sufficient reason to adjust their investment holdings. But the lesson is that trading should be done infrequently: because one of the two counterparties will be proven wrong, it’s unsafe to assume it will always be the other person!

In contrast to the zero-sum nature of trading, investing – owning stocks and bonds for the returns they generate over time through their profits and interest – is a positive-sum game at which every participant can succeed. Even an investor whose portfolio underperforms the broad market index may still be successful, so long as their investment returns meet their goals.

1) The bid/ask spread is the gap, at any time, between the highest price bid for a security’s purchase and the lowest price asked for its sale by another party. The bid price lies below the ask price. The spread essentially represents the cost (excluding commissions) of a round-trip transaction that leaves the investor back where they started.

For example, if the market doesn’t move in the interim, an investor who buys securities at the (higher) ask price and immediately sells those securities at the (lower) bid price will, after both transactions, hold no securities. But they’ll have lost on each security the difference between the higher buying price and the lower selling price, the bid/ask spread.

For example, if the market doesn’t move in the interim, an investor who buys securities at the (higher) ask price and immediately sells those securities at the (lower) bid price will, after both transactions, hold no securities. But they’ll have lost on each security the difference between the higher buying price and the lower selling price, the bid/ask spread.

2a) The zero-sum nature of trading in secondary market with a fixed supply of securities is slightly more complex than first explained in the Main section but its conclusion is unchanged: for the investor making a trade to be right, their counterparties must collectively be wrong.

We disregard those instances in which an investor deploys outside savings into new investments, or in which a seller doesn't reinvest but instead removes their sale proceeds from the secondary market, because those types of trades represent a very small portion of overall trading volume.

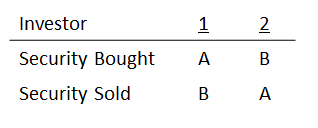

We focus instead on an investor who must fund their purchase with the same dollar-sized sale of a different security. Thus Investor 1 doesn’t just buy security A from Investor 2. Instead, Investor 1 buys security A with the proceeds from their sale of security B. Investor 2 does the opposite and buys security B with the proceeds of their sale of security A. These transactions leave the total supply of all securities in the secondary market unchanged.

We represent these transactions below:

We disregard those instances in which an investor deploys outside savings into new investments, or in which a seller doesn't reinvest but instead removes their sale proceeds from the secondary market, because those types of trades represent a very small portion of overall trading volume.

We focus instead on an investor who must fund their purchase with the same dollar-sized sale of a different security. Thus Investor 1 doesn’t just buy security A from Investor 2. Instead, Investor 1 buys security A with the proceeds from their sale of security B. Investor 2 does the opposite and buys security B with the proceeds of their sale of security A. These transactions leave the total supply of all securities in the secondary market unchanged.

We represent these transactions below:

If investor 1’s view proves correct and security A outperforms security B, then Investor 2 is worse off than had they not traded: they sold security A to acquire security B, which then did worse than A. Investor 1’s benefit from the trade comes at investor 2’s expense.

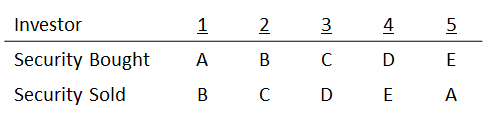

2b) The conclusion doesn’t change even after we introduce multiple investors and securities to make things much more realistic. The table below shows the results when five investors (out of potentially millions) and five different securities (out of potentially thousands) are involved in the set of transactions that allows investor 1 to buy A and sell B:

In this example, investor 2 funds their purchase of security B through the sale of security C to investor 3, who funds its purchase with the sale of security D to investor 4, etc. It falls to someone further down the line, investor 5, to sell security A to investor 1. This set of transactions leaves leave the total supply of all securities in the secondary market unchanged.

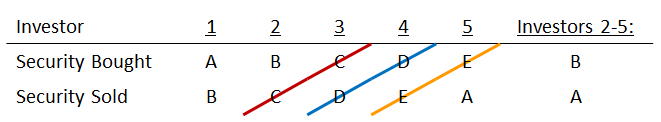

The overall effect is easier to see if we net out each sale and corresponding purchase among investor 1’s counterparties, investors 2-5, using the colored diagonal lines:

The overall effect is easier to see if we net out each sale and corresponding purchase among investor 1’s counterparties, investors 2-5, using the colored diagonal lines:

Investors 2-5 collectively buy security B and sell security A, the opposite of investor 1. If investor 1’s trade succeeds and security A outperforms B, investors 2-5 are collectively worse off than if they hadn’t traded. A’s success comes at the collective expense of investors 2-5, and trading remains a zero-sum game.

2c) The results don't change if we introduce different time-horizons or holding periods among the various investors. Assume that investor 1 buys security A, sells security B and plans to hold for a year. Investor 2 does the opposite, sells A and buys B, but plans to sell B after only one month. Let’s further assume that security A outperforms security B for the year as a whole but underperforms B in the first month.

At first glance it seems that investors 1 and 2 both succeeded: A outperforms B over the entire year, investor 1’s goal, and B outperforms A for the first month, investor 2’s goal.

But this is incomplete: when investor 2 sells security B after the first month, another investor or series of investors must buy and then own security B for the rest of the year. Someone must own security B; it doesn’t just disappear!

Because investor 1’s trade succeeds and A outperforms B over the entire year, the cumulative return to all of B’s owners over the year will be less than that of security A. Investor 2’s successful timing just pushes more of B’s underperformance onto its later owners. Investor 1’s successful trade still comes at the collective expense of all those who own B throughout the year, even though some (like investor 2) do better than others.

At first glance it seems that investors 1 and 2 both succeeded: A outperforms B over the entire year, investor 1’s goal, and B outperforms A for the first month, investor 2’s goal.

But this is incomplete: when investor 2 sells security B after the first month, another investor or series of investors must buy and then own security B for the rest of the year. Someone must own security B; it doesn’t just disappear!

Because investor 1’s trade succeeds and A outperforms B over the entire year, the cumulative return to all of B’s owners over the year will be less than that of security A. Investor 2’s successful timing just pushes more of B’s underperformance onto its later owners. Investor 1’s successful trade still comes at the collective expense of all those who own B throughout the year, even though some (like investor 2) do better than others.

3) Transactions between investors and the security's issuer are not zero-sum because, for example, an issuer typically doesn’t use its sale proceeds to buy another security but instead uses them to make real investment in its operations. However, trades of this type are a tiny fraction of overall security trading volumes, particularly in the stock market. For example, data from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) website shows that each year from 2009 to 2020 the dollar volume of stock trades was at least 200 times higher than the dollar amount of net new stock issuance.

There was a significant double-counting issue with NASDAQ trade volumes prior to 2001 because NASDAQ is a dealer market. When a securities dealer buys a share into its own inventory because there's no other buyer available, and then subsequently sells the same share, two transactions are recorded even though the dealer may own the share for only a few seconds. The advent of electronic crossing networks which directly match buyer and seller should have largely eliminated this double-counting of trade volumes, but we’ve been unable to find any study conducted in the last decade pertaining to this issue.

Even if we assume that every transaction on every exchange is double-counted, which is highly unrealistic, that still renders each year’s stock trading volume at least 100 times larger than its corresponding stock issuance. Over 99% of stock trades occur among stock market participants and not with security issuers, and thus are of a zero-sum nature.

There was a significant double-counting issue with NASDAQ trade volumes prior to 2001 because NASDAQ is a dealer market. When a securities dealer buys a share into its own inventory because there's no other buyer available, and then subsequently sells the same share, two transactions are recorded even though the dealer may own the share for only a few seconds. The advent of electronic crossing networks which directly match buyer and seller should have largely eliminated this double-counting of trade volumes, but we’ve been unable to find any study conducted in the last decade pertaining to this issue.

Even if we assume that every transaction on every exchange is double-counted, which is highly unrealistic, that still renders each year’s stock trading volume at least 100 times larger than its corresponding stock issuance. Over 99% of stock trades occur among stock market participants and not with security issuers, and thus are of a zero-sum nature.

4) Even though trading in aggregate is a zero-sum game, a trade may have a high probability of success for an individual if they have superior information about a security. Insider trading laws restrict the ability of corporate insiders to trade using information to which they are privy but the general public is not.

Until 2000, stock issuers in the US could and did make “selective disclosure” by giving advance warnings about earnings results and other material nonpublic information to a small group of security industry analysts and institutional investors, typically on conference calls from which the general public was excluded. In October 2000 Regulation FD (Fair Disclosure) came into effect, which requires US stock issuers who disclose material nonpublic information to one set of parties to simultaneously disclose that same information to the general public.

Until 2000, stock issuers in the US could and did make “selective disclosure” by giving advance warnings about earnings results and other material nonpublic information to a small group of security industry analysts and institutional investors, typically on conference calls from which the general public was excluded. In October 2000 Regulation FD (Fair Disclosure) came into effect, which requires US stock issuers who disclose material nonpublic information to one set of parties to simultaneously disclose that same information to the general public.